The press is the heart of the handloading operation, also traditionally the most expensive single tool employed (although with the arrival of combined electronic powder scales / dispensers and expensive custom die sets, that’s no longer always true).

Affordability aside, its size, weight, power, precision, ergonomics affect the activity profoundly in terms of the weight and size of the bench needed to mount it, ease of use and of course results – in terms of consistent sizing and concentric bullet- seating. There is no benefit in buying a 30lb cast iron monster that’ll handle the 50BMG or a complex progressive model to neck-size the 6BR, likewise if you choose too small a model for heavy-duty sizing and swaging. So, getting this purchase right is important but what are the key product attributes and how do we rate competing models?

The first issue of course is what needs have to be met – a progressive press that can produce two or three hundred barely 1-MOA capable rounds an hour doesn’t address mine, whilst my arbour and single-stage presses would be equally unsatisfactory to high volume consumers of 223s for CSR, US Hi-Power Service Rifle and similar, not to mention most pistol-cartridge reloaders. Although Target Shooter covers all sorts of paper-punching activities, this review is of three presses that can produce rifle rounds to a potentially very high specification (sub quarter-MOA capable). As for genre, they fit in the medium to large single-stage category, capable of full-length resizing everything up to 30-06 and standard magnums. Bullet-seating requires precise alignments but little effort, so press size and power are really determined by case-sizing requirements.

Even so, this trio may well be larger than my modest needs, or at any rate 99% of my handloading since I’m overwhelmingly a user of small to medium size cartridges. Still, some over-specification is always better than too little, with the tool kept inside its stress comfort zone to produce sized brass and finished rounds with little or no neck/bullet run-out – assuming the employment of quality dies and brass.

If you don’t load anything much bigger than 308, or maybe even 284 Win sized cartridges for precision work and somewhat larger case numbers for field shooting, the mid-size Hornady Lock-N-Load Classic O-frame is an excellent and very ergonomic design at £160 or thereabouts and, the bigger, heavier Lee Classic Cast, also an O-frame type is cheaper still at £120 (prices from UK Benchrest Association competitor Mark Ellis, aka 1967spud.com). Against that, the most expensive member of the trio I’m looking at here costs double the Hornady’s price and you can add another £20 for a near-essential accessory. That’s if you can find anybody stocking this model – the Forster Co-Ax – as they’re usually on back-order from the US manufacturer.

Green Machines

When I think of how much change there has been amongst the manufacturers of ‘consumer durables’ during my lifetime, companies – not to mention whole industries – dying or rising from nowhere, American loading-tool manufacturers seem to be a pretty long-lived bunch, perhaps because they started as one-man outfits and usually remained independent family owned private companies for a generation or two, a few remaining as such. RCBS, Lee Precision and Hornady started after WW2, but Forster (as Bonanza) and Lyman (as The Ideal Tool Co.) go back much further. Another peculiarity is that they mostly paint their stuff in a small range of colours (or have them mixed into the increasing amount of plastics used) – red for Forster, Hornady, and Lee; green for Redding and RCBS. Lyman’s orange is the odd colour out and, its presses are finished in a mixture of black and hammer finish silver-grey these days.

Evolution

Product development for the classic bench-press is a mainly evolutionary, only rarely a revolutionary process that sees few newcomers – something produced way back that the punters like, listen to user feedback and follow trends in the size/nature of cartridges being loaded and incorporate useful improvements every five or ten years. Maybe make components like frames and rams more accurately to closer tolerances through CNC machining … and so on.

It was that rare event – a new, completely different design appearing – that started this review off some time back. Surprisingly, to me at any rate, it came from the Microsoft of reloading tools rather than the Apple – RCBS that is. A few years back, the RCBS range consisted of four single-stage models from the little ‘Partner’ to the big ‘AmmoMaster’ (which can handle 50BMG), a turret design, and a progressive – actually, maybe more than one progressive (since increased to three models).

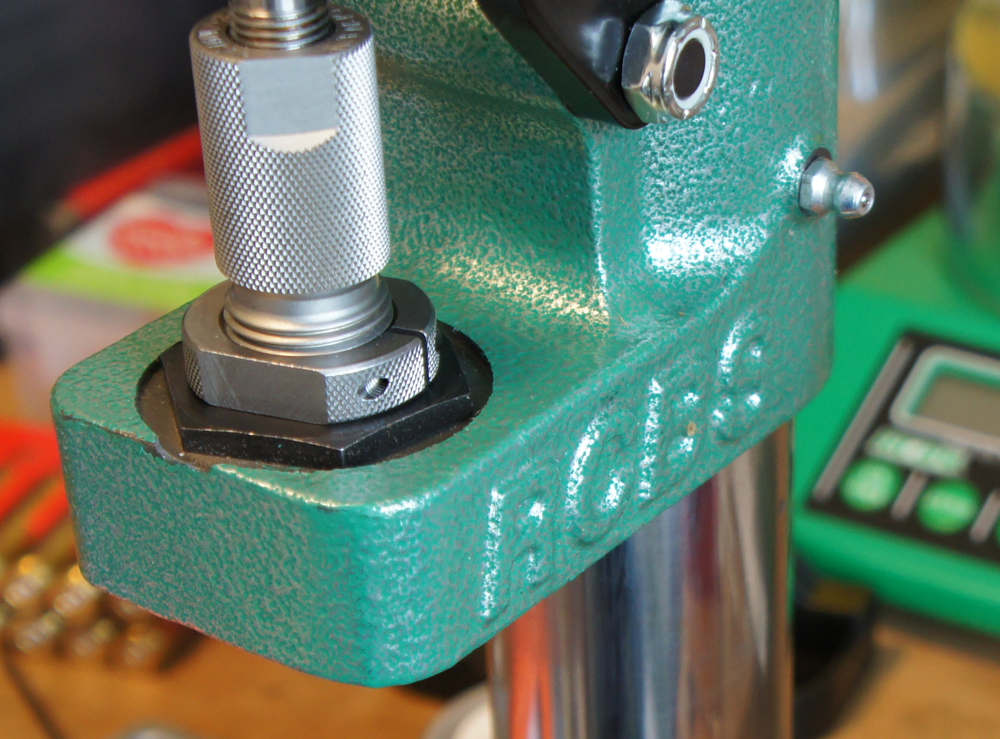

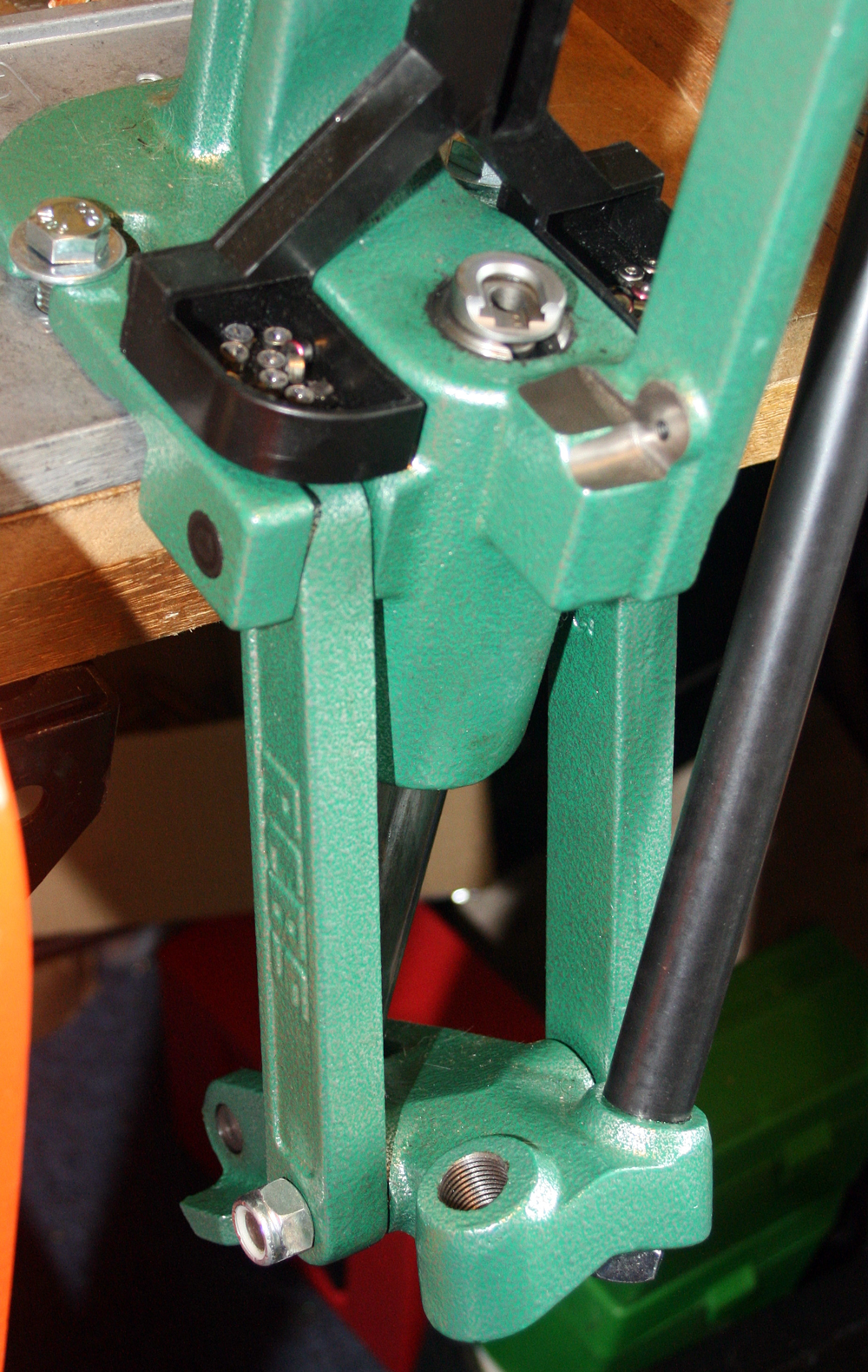

The mainstay of its rifle cartridge presses was the single-stage Rock Chucker, a venerable heavy-duty O-frame type that had been upgraded some time before to the Rock Chucker Supreme, its frame height increased to give a 4.25-inch opening to handle the new breed of long ultra-mag cartridges, improved spent-primer collection and a new bottom end arrangement for ambidextrous operation.

In this form, it is a large, heavy and very powerful machine weighing in at nearly 20lb.

There was a rather large gap between the RC-Supreme and the next press down in the single-stage range, the much lighter (~8lb) RS-5 model with nothing matching other manufacturers’ middle of the range O-frames that typically weigh 13 to 15lb such as the Hornady Lock-N-Load Classic and Redding Big Boss. So, when the company announced the launch of a new single-stage press at SHOT 2013, one might have expected another O-frame filling the gap – but not so.

Upside-Down

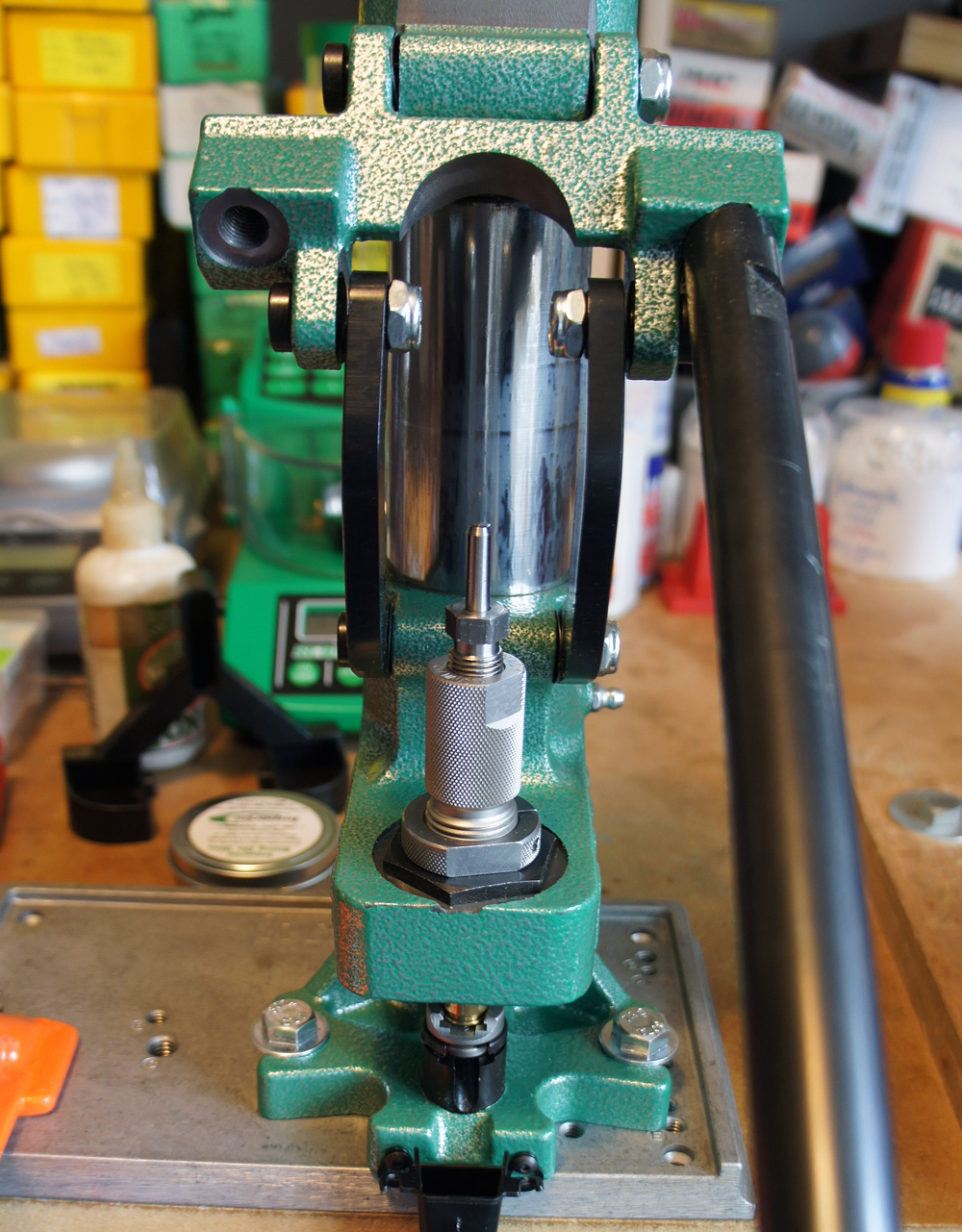

It was a C-form press that appeared instead, albeit nothing like a conventional model. It’s an innovative design that puts a static shellholder mount on the base-plate and, instead of the usual fixed die-position in the frame, has it on a moving platform directly connected to the top-mounted handle via simple operating links. There is no ram as such, this component replaced by a massive three-inch diameter machined steel column, the die-platform moving down it on handle operation, thereby taking the tool to the case.

The Summit Press – as it’s named – is an upside down machine if you like, turning a whole pile of press operation conventions on their head. Moreover, this is a press without a conventional frame, no exoskeleton one could say, the steel column being the vertical ‘leg’ of the C, the die-platform and base-plate its horizontal ‘arms’. The press’s operating handle is attached to a large hinged cast-iron boss on its head with twin parallel curved steel links to the moving die-platform. As with the RC-Supreme, the boss is drilled and tapped on either side of the column to allow left or right hand handle mounting for ambidextrous operation. The long handle operates through a near 180-deg arc pointing slightly behind vertical at rest, moving to the horizontal position when the case is well into the die before needing another 12 or 13-deg downwards movement to fully size a case. It is a large machine with a 4½-inch gap able to physically encompass the longer magnums up to the 338LM, and weighing even more than the Rock Chucker at 21½lb.

The C-frame press’s upside is its open layout – giving easy access with either hand to shellholder, case, hand starting the bullet in the case-mouth. The downside – loss of strength/rigidity compared to a closed O-form casting. The massive nature of the Summit’s main assemblies should overcome this, one imagines looking at the beast.

The layout has two great pluses over any other bench model I know of – its vertical column form reduces the tendency to be pulled over towards the user when working hard so it manages with a small mounting area by normal standards and a two bolt fixing set-up. With its upside-down reversed layout, nothing hangs below the base, therefore below the bench-top, facilitating the use of space underneath. It also suits temporary mounting on say a dropped pick-up tailgate or other alfresco platform for those camping out and loading ammo on-range.

Price-wise, it sits between the other two, the Rock Chucker Supreme at £180-200, the Summit listed around the £220 mark and the Forster Co-Ax much pricier at £320. Because of the high operating handle positions on Summit and Co-Ax models, their manufacturers offer a short handle as an optional accessory costing around £20, and such is their usefulness, I’d recommend anybody contemplating either press to factor this addition into the costings.

RC-Supreme and Co-Ax

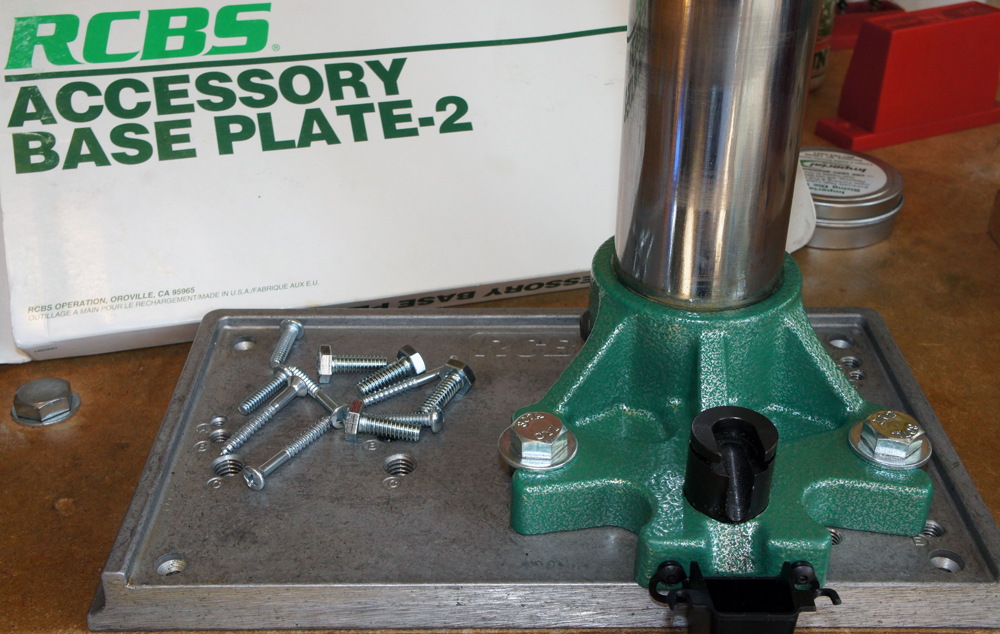

Any shooter who has ever used a conventional single-station bench press will be at home with the RCBS Rock Chucker Supreme. Unlike many who started out in handloading with the old RC model (and usually never seen any need to try anything else subsequently), I’ve never owned one and never had the chance to use one prior to this test. I’d received the loan of the new Summit thanks to Alan Baldry, ATK Alliant’s man in Europe as none was being imported at the time. Alan also added the RC-Supreme and an RCBS Accessory Base Plate-2 – the former to compare the Summit press against, the latter to facilitate bench mounting, being already drilled and tapped for both models (as well as various other RCBS presses and devices including the bench priming tool, case trimmer, Uniflow measure and more) with the fixing bolts included.

Alliant ATK – that’s the huge US based multinational that makes missile parts, propellants and explosives and whose sporting division includes the former Blount Inc. activities of which RCBS tools is part. I took to the Rock Chucker straight off and can well understand its enduring popularity, easy to operate and works very smoothly and efficiently.

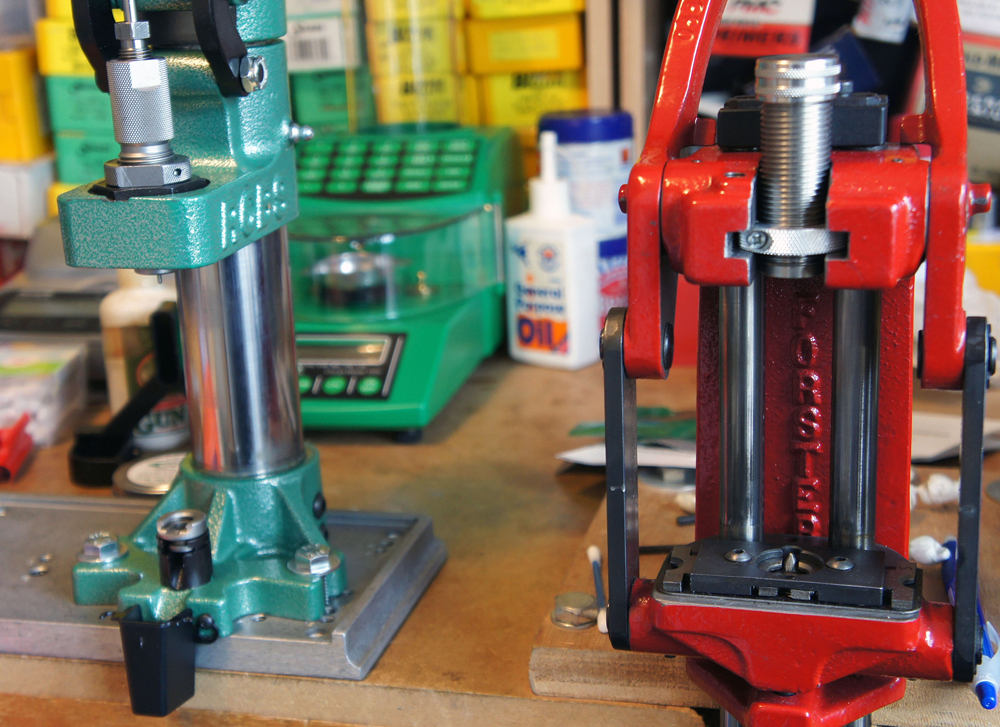

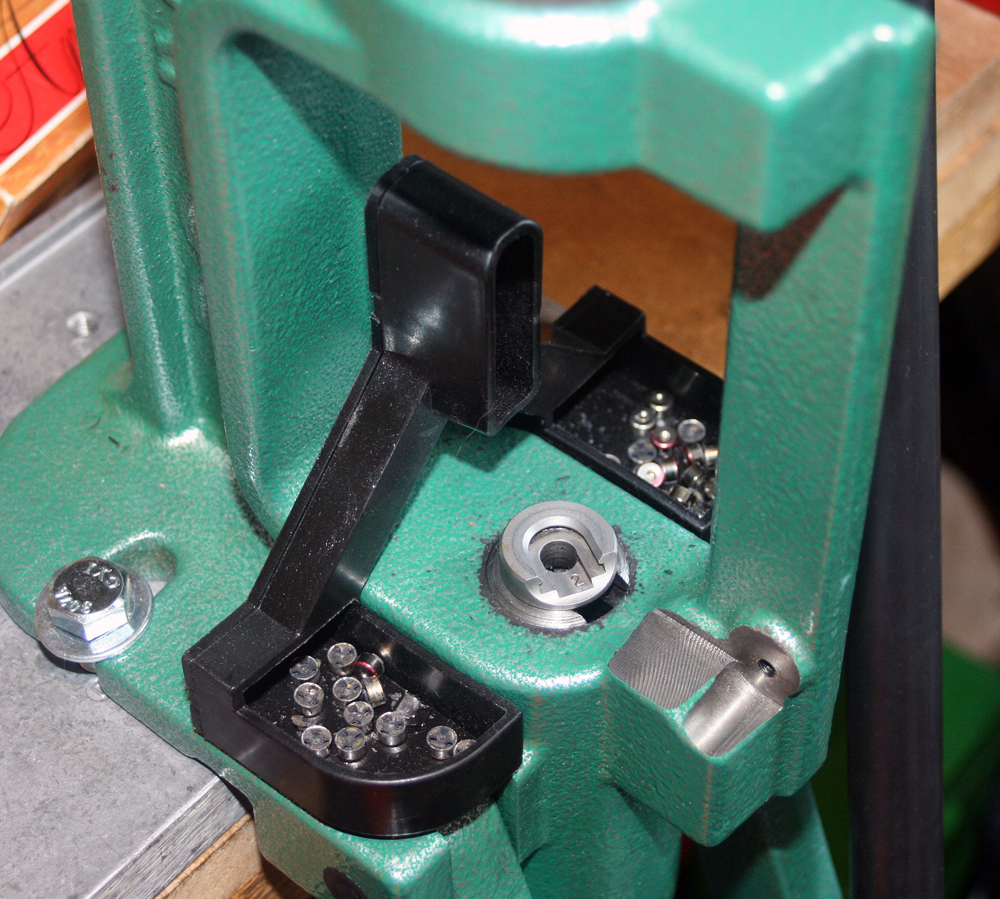

Like the RCBS Summit, the Forster Co-Ax is another design oddball, a C-form but also unlike other examples of the genre. It lacks the traditional ram, the two fixed horizontal ‘arms’ of the frame and the moving assembly that incorporates the shellholder held in precise alignment by twin vertical steel rods pinned to the latter and sliding through holes in both lower and upper frame ‘arms’, all with close tolerances.

Like the Summit, the operating handle is above the machine, located centrally here and there are again twin steel links at the top end of the press dropping down to the moving parts. The Co-Ax incorporates a number of novel features, principally its automatic and multi-case compatible shellholder assembly with spring-loaded sliding jaws, very neat spent primer arrangements that allow hardly any gritty residues to escape and foul the moving parts and, the snap-in/out die fitment that allows rapid changes and also sees the die ‘float’ in relation to the case giving very concentric results. I own this press and it meets my handloading needs very well.

Testing Times

This trio make light work of bullet seating and, I’d be frankly amazed if any produced non-concentric results – assuming good quality and well-sized brass allied to a good die. With the optional short handle installed, I’d reckon the Co-Ax the most ergonomic in this task but I would say that wouldn’t I, given that this is my own press?

The Summit really needs its short handle for light duty case/neck sizing and bullet seating, the standard one being very long and needing a high seating (or low press mounting) position to avoid a lot of stretching.

So, I was going to judge them subjectively and also partly objectively on how well and easily they did some full-length sizing. Objectively? This was measured by the amount of case-shoulder ‘bump’ the three produced with the die adjusted to the default position in hard contact with the shellholder. Also, the degree of consistency in sized case-shoulder positions using a Hornady comparator and appropriate ‘headspace gauge’ (actually it’s not, rather a case gauge). I’d also run the finished results over a Sinclair concentricity gauge to measure neck runout to see if any differences showed up.

Ideally, I needed a quantity of largish cases fired in a rather slack chamber preferably from a factory rifle or rifles – not much of a test sizing 6.5X47 Lapua brass or even my 308 Lapua Palma stuff all cosseted and fired in minimum SAAMI or similar custom rifle match chambers. After some deliberation, I settled on a heterogeneous collection of 7X57mm cases I’ve built up over time and which I needed to size anyway.

There were three main batches involved: RWS and Norma from some quite ancient lots which would have been loaded to full CIP pressures. (The Norma was decidedly ‘poky’ in fact in a vintage 1950s BSA Hunter – don’t let anybody fool you with the old 7mm Mauser is ‘a gentle cartridge’ guff, it only gives light recoil in low power loadings same as any other design). The third main lot was some recent manufacture once-fired Federal brass from factory ammunition that I’d bought through the SD Forum classifieds. Having been fired in a modern sporting rifle and given most American ammunition companies’ worries about this 19th century cartridge design being fired in a genuine (and knackered) 19th century smokepole reflected through anaemic loadings, these cases would have been only lightly stretched both literally and figuratively.

However that certainly didn’t apply to some of the European brass. Whilst the aforementioned BSA is very tightly breached in headspace terms, it turned out in retrospect that the opposite had obviously been the case with an old Mauser 2000 rifle I’d previously fired all of the RWS and some of the Norma factory ammo in. One very elderly box of RWS ammo showed case stretch marks warning of imminent case separation and, a carton of modern American PMC ammo fired in the same piece of junk had badly backed out primers (the loadings not being hot enough to fireform/stretch the brass fortunately).

So, the cases that had been fired in this rifle needed shoulders bumping by getting on for 20 thou’ instead of the usual low single figures you’d expect. Suddenly, the FL sizing task had become much harder! Case batches were split equally amongst the three presses, the numbers assigned to each being 10 RWS, 13 Federal and 10 Norma fired in the excessive-headspace Mauser chamber with another 10 fired in the ‘tight’ BSA. So each press was tasked with 20 cases needing ‘heroic’ sizing and 23 with a stiff, but not massive requirement.

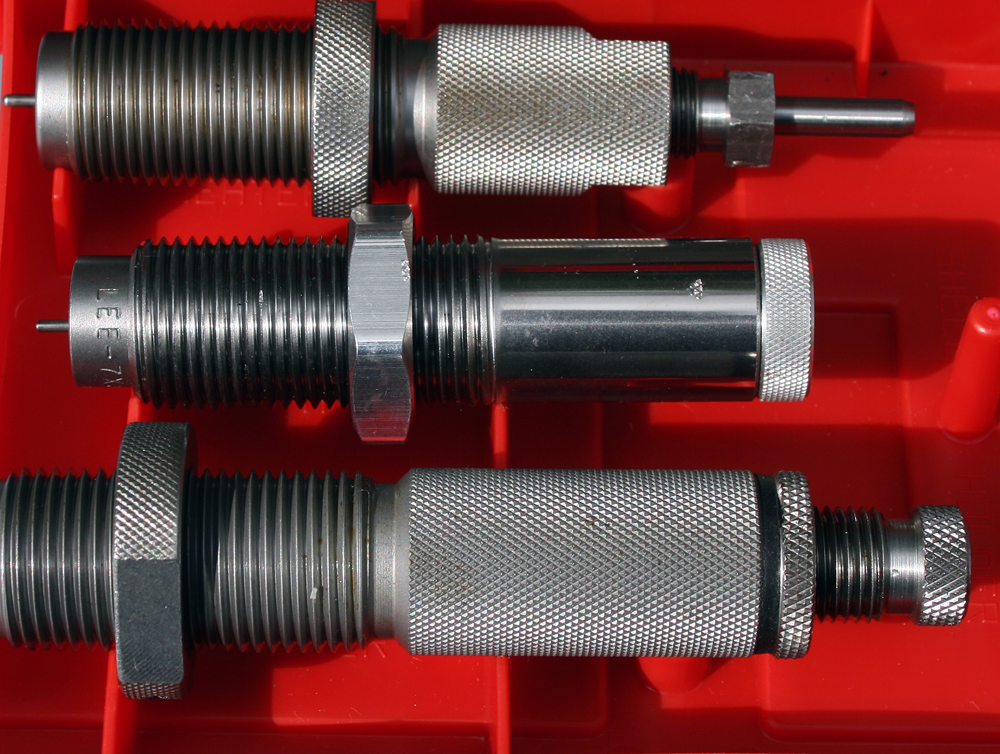

Some other fired brass from Hirtenberger and PMC lots was used to set the die up in each press. The full-length sizer die employed was recent manufacture standard Hornady, a well made bit of tooling with a highly polished and gently tapered expander ‘ball’ that reduces the case extraction/expand workload. It had seen very little or no use beforehand and was thoroughly degreased and cleaned before this exercise. My usual Imperial Die Wax was the case-lube.

Ruminations

Before getting onto how well the presses coped, there are a couple of points worth examining here. Most people assume that screwing the sizer die down until it’s in hard contact with the shellholder and the press linkage ‘cams over’ on full handle operation will size the case ‘the right amount’ and also produce very consistent results so far as shoulder position goes – and, following from that, a consistent ‘case to chamber’ headspace relationship. Well, it’s not necessarily so on either count.

The default setting may set the case shoulders back too much producing an excess headspace condition – at the very least this won’t help precision and it’ll quickly ruin cases if serious enough. The ideal ‘case shoulder to chamber’ clearance is 0.001-0.002” for a precision bolt-gun – a bit more for semi-autos/straight-pulls. There are various methods to measure clearances and set dies up to optimise them but that’s another subject. So far as the consistency of this key dimension is concerned, we now have loading tools that are far better suited to achieving them relatively easily than was the case not too many years back. Nevertheless, shoulder position consistency can never be taken as a given even by a conscientious and careful handloader using good tools.

I recently reread an old Precision Shooting magazine article selected for The 1995 Precision Shooting Annual called Feeding Your Service Rifle by Ronald A. Yerian and Mike Stiverson. The ‘Service Rifle’ was the 308 Win calibre M1A/M14, the then standard model used in US NRA Hi-Power Service Rifle XTC competition. Despite being semi-auto military rifles, specialist gunsmith rebuilding and modification was required to be competitive, so we’re talking carefully built match rifles here that needed annual fettling to remain ‘in tune’ too. Mr Yerian was an experienced handloader who took on the job of producing 308 ammunition for his teenage son who’d been selected for a junior team, but soon found that this apparently straightforward task was anything but – his homeloads shooting saucer size groups with infuriating ‘fliers’ beyond that.

The best commercial match ammunition then available, Federal Match loaded with the 168gn Sierra MK bullet, reliably shot to 1-MOA, so Mr Yerian got into the measurement business to see what it had and his own efforts lacked given that load combinations weren’t the problem – everybody including Federal using a small number of case, primer, bullet, and powder recipes. Buying RCBS’ Precision-Mic case ‘headspace’ gauge and CaseMaster measuring tools, he delved into the world of shoulder positions, case-neck and bullet run-out values as well as dimensional and weight consistencies.

Federal factory match measured:

Headspace: -0.001 to -0.002”

Max neck TIR: 0.002”

Max Bullet TIR: 0.005”

Other commercial and arsenal ‘match’ rounds were significantly poorer. (TIR = Total Indicated Runout.)

Military M180 type ball from various sources had shoulder position ranges (‘headspace’) ranging from 0.004” at best to 0.008” variations amongst sample cartridges, two to four thou’ case-neck TIRs, and max bullet TIRs of 10 and 11 thou’ in some batches.

Mr Yerian’s early handloads sized using the ‘default’ sizer die setting had shoulder position variations of up 4 or 5 thou’ at best to 11 thou’ in the worst batch. Case-neck maximum TIRs of five to six thou’ in all batches and bullet TIRs of up to 9 thou’ in the better batches to 13 thou’ in the worst!

Bear these levels in mind when I report on how the three presses with a modern off the shelf sizer die performed. (To be fair to Mr Yerian, M1A comp shooters used brass obtained from so-called arsenal match ammunition, certain years’ headstamped Lake City lots particularly favoured, because the M1A/M14 was notoriously hard on brass and relatively soft commercial cases not only wore out quickly, but were more likely to cause rifle functioning problems). In the event, the author eventually made large improvements in his ammunition preparation and its grouping capabilities through trying a lot of dies (and returning some sets as unsatisfactory), accurate die adjustment in the press against fired case readings using the Precision-Mic tool, experimenting with case lubrication and adopting very consistent press-handle operation.

Results

So, back to the present with the three presses, 7X57mm brass and a little used Hornady die set. I’ve always held Hornady ‘New Dimension Custom’ dies in high regard, smooth and low friction in use and delivering excellent results. The expander ‘ball’ has been refined to a long streamlined form over the years and its stem lightly threaded in recent examples to provide a better grip in the retaining collet and ensure concentricity. (My die predated that improvement and has a smooth stem which is prone to slip in the collet unless it is done up really tightly).

Bushing-type match sizers are better still for precision ammunition used in custom match chambers but, these £50 die sets and their equivalents from the other well known makers provide excellent results and meet the needs of most shooters very well. Cases were well lubed with Imperial die wax including the inside of their necks, a pain to do and even more so to remove the film after sizing but a move that transforms the reverse press stroke, making it much easier to pull the case over the expander ball and imparting far less stress on the case.

The Forster Co-Ax

Each press was then used to size 43 cases split 10 / 13 / 20 by RWS, Federal, and Norma respectively, starting with my own Co-Ax. When I bought this press some years ago I also purchased the optional short handle as I rarely do any heavy-duty full-length sizing and it was fitted on day one and has never been off the tool since. Although I full-length or body-size much of my brass, the short handle has been more than adequate with cartridges such as 6BR, 6.5X47L, 6.5mm Creedmoor, 7mm-08 and suchlike. So, the first case fired in the excess headspace and slack Mauser 2000 chamber was a shock – I struggled to operate the press, and the OEM long handle was retrieved and fitted tout suite! This made things much easier but it still couldn’t be in any way described as effortless. The less expanded cases were sized without undue trauma but still took some grunt. If I were doing this regularly, I’d be swapping press-handles routinely, not that it takes more than a few seconds to do so.

The RCBS Summit

So, onto the RCBS Summit and, despite its massive build and long-stroke operating handle, I reckoned it took more sweat than I’d expected, even if it was somewhat less work than with the Co-Ax. I’m not sure I took to the very long handle-stroke but that may have just been a familiarity issue, and my seating position was too low in relation to the press for best ergonomics as well. Although the Summit is apparently massive, I noticed that the die platform would tilt fractionally under the heaviest strains and this showed up as witness marks on the lubricant coating on the smooth press column after the session finished. It is nevertheless a very pleasant press in use and bullet seating was a doddle the few examples tried proving very concentric on checking them afterwards. The optional short handle would be valuable for this task.

The RCBS Rock Chucker

Back to sizing the 7X57 cases and I was getting a little discouraged by now – thank goodness I wasn’t doing a large quantity of 300 Remington Ultra-Mag or 338 Lapua Magnum brass! My expectations of the antediluvian RCBS Rock Chucker Supreme’s performance weren’t over high to be honest as I mounted it in the place of the Summit. As soon as I sized the first of the stretched RWS cases though, I saw why this press has been such a long-running favourite. The workload was considerably reduced compared to the other two presses and doing 40 odd cases took no time at all with little sweat – it just eats hard-to-size brass. Still, ease of operation is one thing, I had to measure the 120 or so cases to see how good a job each press had done, or maybe to find they’d all done an equally good (or poor, but that seemed unlikely) job as each other.

Measurements

So, how did the three get on with the brass? If you look at the table, there’s not a lot between them in neck run-outs but there is a definite trend towards the RC-Supreme extending the range of recorded TIR values by an additional thou’ upwards compared to the other two presses. With regard to shoulder positions, the Rock Chucker Supreme pushed shoulders back further than either of the other two could and produced smaller variations, everything inside a two-thou’ band whereas three was the norm with the Co-Ax and Summit. Interestingly, there was no difference in any of the trio’s results between the two lots of Norma cases – that is the presses produced the same results whether the cases needed a little or lot of shoulder ‘bump’. (That was also reported by Ronald Yerian in the Precision Shooter article comparing brass fired in a defective M1A against that fired in a Winchester match rifle with minimum headspace).

So, in conclusion, if you’re doing a lot of really heavy-duty sizing get the Rock Chucker. The Summit and even more so the Co-Ax are more ergonomic for lighter duty tasks and both have a reputation for very low bullet run-outs after seating and this shows in the case-neck TIRs. The Summit’s USP is its upright profile, minimal mounting area and ability to be mounted where others won’t go. As always, you pays your money and makes your choice! With my handloading needs, I’ll stick to the Co-Ax as it suits me and my cartridges very well.

| Brass | Shoulder Position (L-N-L case gauge D base to shoulder) | Case-Neck TIRs | |

| Forster Co-Ax | 10 x RWS | 1.783” – 1.785” (7 x 1.784”) | 0.001-0.0025” |

| 13 x Federal | 1.782” – 1.784” (10 x 1.783”) | 0.0015-0.0035” | |

| 20 x Norma | 1.783” – 1.785” (16 x 1.784”) | 0.0005-0.004” | |

| RCBS Summit | 10 x RWS | 1.784” – 1.786” (6 x 1.785”) | 0.0005-0.004” |

| 13 x Federal | 1.781” – 1.782” (9 x 1.781”) | 0.0005-0.0055” | |

| 20 x Norma | 1.783” – 1.785” (evenly spread) | 0.001-0.004” | |

| Rock Chucker Supreme | 11 x RWS | 1.782” – 1.783” (9 x 1.783”) | 0.001-0.005” |

| 13 x Federal | 1.779” – 1.780” (9 x 1.780”) | 0.001-0.004” | |

| 20 x Norma | 1.779” – 1.780” (13 x 1.780”) | 0.0005-0.005” | |